Update on May 2, 2017, Tue [Parte 1]

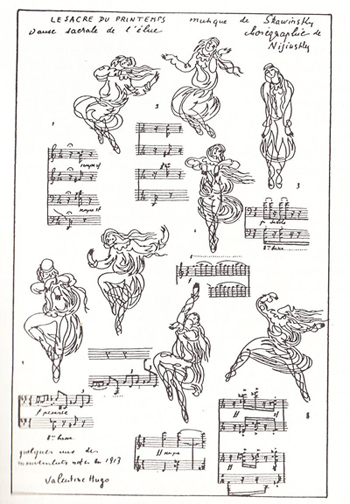

Un gruppo di ballerini posto nella produzione originale di

Le Sacre du printemps (1913)

The music for this brilliant ballet becomes a modern version of the Russian khorovod, dancing chants typical of weddings and spring ceremonies, whose main features are short patterns that may be repeated continuously and combined in different ways and free rhythmic accents that are nevertheless inscribed in the stubborn group dance pace. A caged freedom, in which short patterns or clusters of notes follow each other with surprising unpredictability, taking players’ and listeners’ breath away when they least expect it; it is almost like listening to the transcription of an impromptuceremony sung by many voices, where the material is passed on from singer to singer in countless combinations.

Such a dynamism does not lack mèlos, the leading voice, that stands out as a call in the wild, towering over the seeming cacophony and throwing spells with the bright sound of horns or trumpets.

In this way, the short riffs are fragmented and imperceptibly varied both horizontally and vertically, causing an enormous building that has tonal shape–but not substance– to germinate from such simple patterns. It develops through scales that are similar, but not identical, to the ones two centuries of music have accustomed us, made of dissonant and excruciating shocks as in an austere modal patina.

Still, the technical side, while surprising, is not enough to explain the charm of this score.

Stravinsky’s compositional mastery has too often led the performers of this masterpiece towards interpretations based on structuralism or–even more imaginatively– on serialism.

Drawing of Marie Piltz in the Sacrificial Dance

from The Rite of Spring (1913)

The Rite was actually born for theatre, for dance, for a very specific scenario, for telling a story; many reasons are to be found in the innate ability of the composer to become a poet of a different Russia, ancient and brand new at the same time, as brutal and primitive as only a man from the very modern 20th century could have imagined.

Far from French fl oral decadence, with its antiquities scented of absinthe and incense, Stravinsky imagines a savage prehistory, whose laws are mythological and antirational.

And so here we have the unpredictability of the dancing rhythm, the strident and unusual timbres, as if to imitate the boneflute and skin-drums players; here we have a story of sacrifice, a girl that immolates herself to the gods jumping crazily till death. All this is translated into a music that is reflected in the timeless charm of Russian folklore (Stravinsky’s numerous borrowings from piano collections of traditional tunes and melodies are proven), but that points to the new tonal and rhythmic freedom of the music to come.

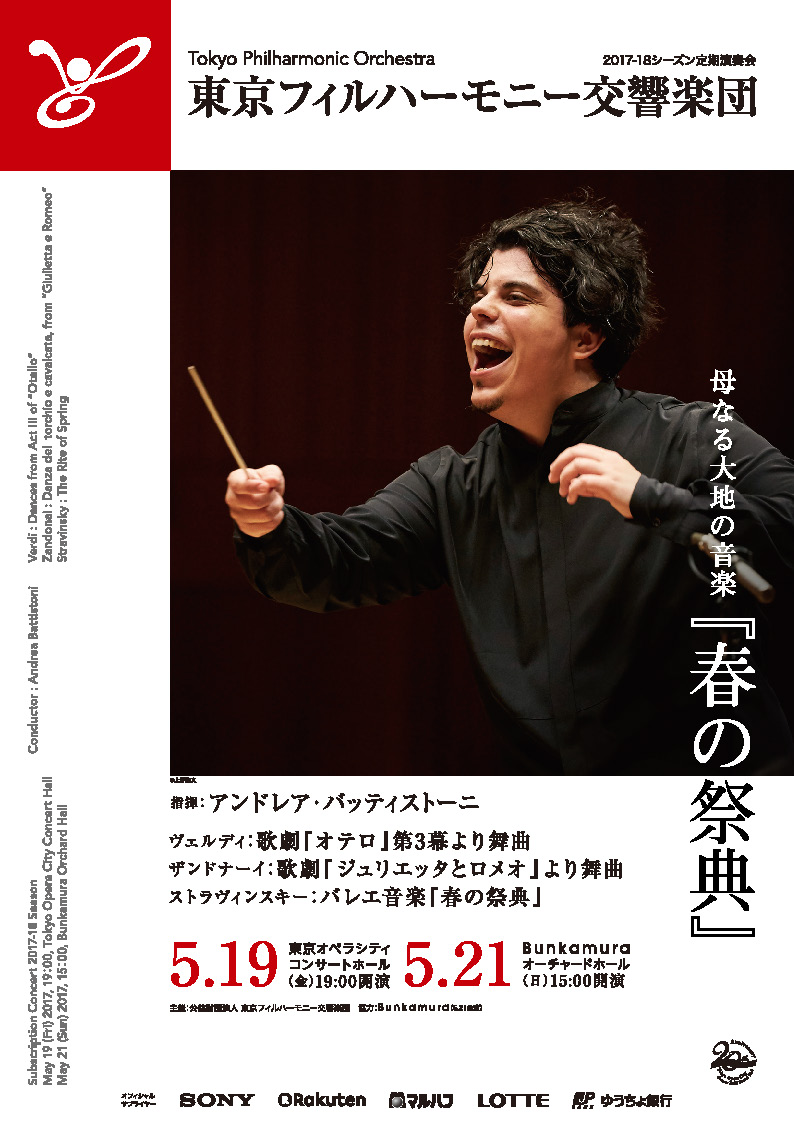

Andrea Battistoni

Chief Conductor of the Tokyo Phil.Orchestra

Shortly afterwards, the musical world would split in two: on the one side, the Austro-German line of Schoenberg–with post-wagnerian tonal dreams that have become sparse representations of the discomfort of the two World Wars–and the expressionism of Berg and Webern; on the other side, Stravinsky, the shaman, with his rhythmic fury that will invite very diverse composers to join him in the dance: Carmina Burana’s Orff, Turandot’s Puccini, from the Spanish De Falla to the American Copland. The Rite of Spring, mysterious union of prodigious technical mastery and visionary power, continues to represent the most vital contribution to the debate on the overcoming of tonality and of symmetricrhythmic structures, a work that amazes scholars for its trove of secrets and listeners for the outbursting energy with which it rips the veil of time to present, in one shot, the past and the future of musical art.

Bibliography

Richard Taruskin, Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions, Berkeley, University of California Press,

1996, cap.12, “The Great Fusion”

Flavio Parisi / Italy to English translation

Italian diction professor at Senzoku College of Music, as well as Italian language teacher at Italian Culture Institute and Opera lecturer at Shukutoku University. He graduated in Oboe at the Music Academy in Udine, under Maestro Pellarin. He has worked as Italian language coach for Tokyo Nikikai Opera Foundation and is active as musician in Tokyo and Italy.

Next Concert

The 109th Subscription Concert in Tokyo Opera City

May 19, 2017, Fri 19:00 start

Tokyo Opera City Concert Hall

The 892nd Subscription Concert in Bunkamura

May 21, 2017, Sun 15:00 start

Bunkamura Orchard Hall

Conductor: Andrea Battistoni

(Chief Conductor of the Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra)

Verdi: Dances From Act III of “Otello”

Zandonai: Danza del torchio e cavalcata, from “Giulietta e Romeo”

Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring

Presented by Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra

Supported by ![]() the Agency for Cultural Affairs Government of Japan

the Agency for Cultural Affairs Government of Japan

In Association with Bunkamura (only May 21)

![BUY TPO TICKETS [03-5353-9522] Business hours: 10:00~18:00 Regular holiday: Sat・Sun・Holiday](../../img/common_en/bnr_inquiry2.png)