INFORMATION DETAIL

Update on October 4, 2022 (Tue)

The world of opera is filled with great tragedies: Verdi’s Otello, Bellini’s Norma, Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, Puccini’s Tosca, Britten’s Peter Grimes, and Berg’s Wozzeck just for starters. But what about comedies? How many truly great comedies are there? Very few. At the top of the list is surely Verdi’s Falstaff. There are no “big issues” here, no profound character development, no domed love ̶ just an engaging story filled with fun and frolic, youthful high spirits, memorable characters, scintillating music, and rapid-fire dialogue (no repeating the same words over and over!). Falstaff is an opera almost impossible not to love.

Verdi’s 26 operas were not evenly spaced across his career. Between 1839 (Oberto) and 1850 (Stiffelio) he turned out an opera a year, sometimes two. Beginning with Rigoletto in 1851 the spacing began to get wider. There were six more until 1862, then just four more over the next thirty years. With Otello in 1887, Verdi truly thought he had done enough, and looked forward to living out the rest of his life in quiet comfort (in fact, he lived right into the twentieth century, dying at the age of 87 in 1901).

But there was one final masterpiece waiting to be born, and it was Verdi’s librettist for Otello, Arrigo Boïto (also composer of Mefistofele), who was largely responsible for its conception. Boïto knew that Verdi had long wanted to write a comedy. He also knew of Verdi’s profound love of Shakespeare. The bait Boïto dangled in front of Verdi consisted of his adaptation of the bard’s comedy The Merry Wives of Windsor (condensing here, expanding there), laced with monologues from Henry IV Parts I and II. The result, first presented on February 9, 1893 at Milan’s La Scala, was predictably a roaring success. Notables from all over Europe attended. Tickets went for incredible sums. The applause afterwards lasted an hour. Falstaff was given 23 more times in its first season alone at La Scala.

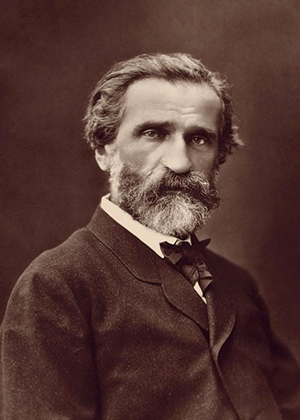

Giuseppe Verdi

(1813-1901, by Ferdinand_Mulnier)

Falstaff was quickly recognized for what it is ̶ a magnificent synthesis of poetry, drama, and music, much in the manner of a Wagnerian music drama but without all the mythological and philosophical baggage. The action is swift. the design is compact, there is not a single wasted moment. Every word is important, and the orchestra is an equal partner

with the singers. In fact, the orchestra is probably more important in Falstaff than in any other Verdi opera, providing continuous commentary on the action and a vast array of colors to match the mood at any given moment. Often the music flies by so fast that it takes multiple hearings to catch it all, but a few moments stand out. In the first scene, for example, when Falstaff looks in his purse for coins to pay the tavern-keeper, he discovers it is nearly empty, a notion reflected in the orchestra by horns alone, sustaining widely-spaced long tones to create the sensation of “emptiness” (no notes in between). Introducing Scene 2 is a deliciously appropriate bit of orchestral writing that perfectly sets the mood of frivolity for the capricious, chattering ladies we are about to meet. Perhaps the most memorable moment for the orchestra occurs at the conclusion of Falstaff ’s opening monologue in Act III. As the wine he is drinking begins to take effect, warming his body and mellowing his spirit, a single flute begins to trill. More flutes, then more woodwinds, strings, and finally the entire orchestra ̶ even trombones! – join in to paint the unmistakable picture of Falstaff having returned to his jolly old self.

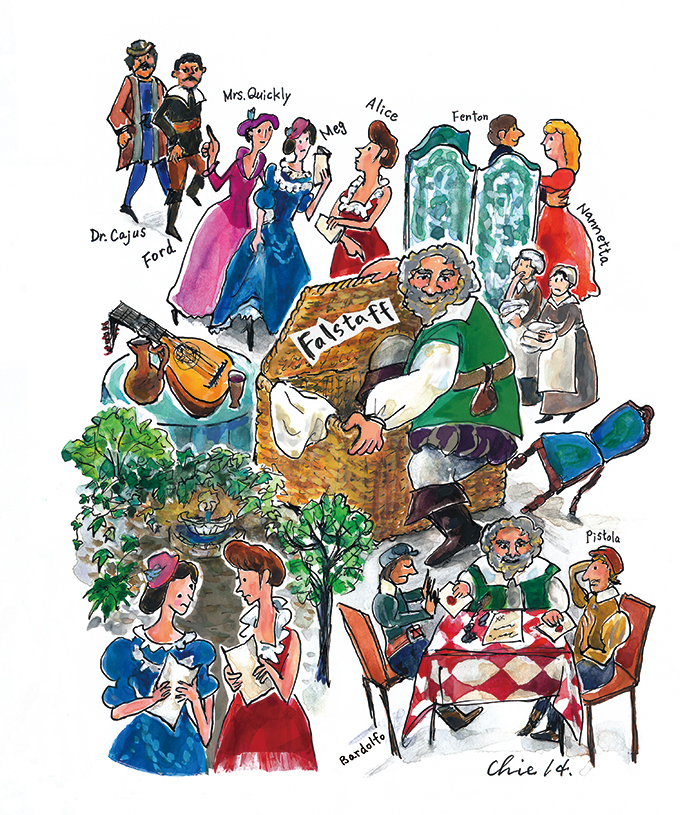

There are ten characters in the opera, and all have important parts. There is an almost constant coming-and-going of cast members, and numerous ensemble passages ̶ even several rare examples of nonets. For this reason it is one of the most difficult operas in the repertory to conduct, to prompt, to direct, or in which to manage the surtitles (or sidetitles). There are no passages suitable for excerpts on operatic or vocal recital programs, either because they are too short, lack tidy endings, or just don’t work out of context (Ford’s and Falstaff’s monologues, for example).

Falstaff has been called “among the loveliest dreams of yesterday ever imagined by the mind of man … It has the mobility of mercury and the durability of silver, and sounds as a combination of those two might come from a sorcerer capable of converting a sensation of the hand into a sensation of the ear.” (Irving Kolodin)

Kolodin’s reference to a sorcerer is apt. Verdi magically transformed the whole world of Italian opera. Even his early opera Nabucco (Verdi’s third and the one that made him famous) has a raw energy that went far beyond what Italians were used to hearing in their bel canto repertory. The orchestra was larger and more powerful, the singers had more forceful and strongly defined roles, and the entire opera was deeply imbued with dignity, monumental strength, tragic pathos and Biblical grandeur. These qualities carried over into many of Verdi’s subsequent operas. The transformation of Italian opera reached even greater heights with the great central trilogy of Rigoletto, Il trovatore, and La traviata. With these, Verdi became the only opera composer who could rival the French Meyerbeer, and by far the most popular Italian composer of the mid nineteenth century.

Verdi’s public life was not limited to the world of opera. He was deeply involved with a political and social movement known as the Risorgimento, whose purpose was the overthrow of Austrian domination and unification of the various Italian city-states into a single country. Verdi lived to see his dream come true: Italy became a unified country in 1861. He was briefly a member of the country’s first Parliament, and even his name was turned into an acrostic symbolizing his nationalistic sentiment: Vittorio Emmanuele, Re D’Italia (Victor Emmanuel II was King of Sardinia from 1849 to 1861 and became the first king of a united Italy in 1861). When Verdi died, forty years after unification, all Italy went into mourning. For the interment of his body in the crypt of the Casa di Riposo in Milan, a crowd of more than a quarter of a million gathered for the event. Verdi the man was gone, but his legacy lives on, with operaphiles around the world loudly singing the praises of Falstaff as one of his greatest achievements.

Robert Markow

Formerly a horn player in the Montreal Symphony, Robert Markow now writes program notes for that orchestra and for many other musical organizations. He taught at Montreal’s McGill University for many years, has led music tours to several countries, and has written for numerous leading classical music journals.

October Subscription Concerts

Oct. 20, Thu 19:00 start

Suntory Hall

Oct. 21, Fri 19:00 start

Tokyo Opera City (Concert Hall)

Oct. 23, Sun 15:00 start

Bunkamura Orchard Hall

Conductor: Myung-Whun Chung

(Honorary Music Director)

Sir John Falstaff: Sebastian Catana

Ford: Shingo Sudo

Fenton: Yusuke Kobori

Dr. Cajus: Tetsutaro Shimizu

Bardolfo: Takashi Otsuki

Pistola: Hirotaka Kato

Mrs. Alice Ford: Ryoko Sunakawa

Nannetta: Rie Miyake

Mrs. Quickly: Ikuko Nakajima

Mrs. Meg Page: Yumiko Kono

Chorus: New National Theatre Chorus

Verdi: Opera "Falstaff" in concert style

![BUY TPO TICKETS [03-5353-9522] Business hours: 10:00~18:00 Regular holiday: Sat・Sun・Holiday](../../img/common_en/bnr_inquiry2.png)